The revelation in the rereading

The Bible offers the Word of God in texts which have been elaborated in the course of centuries. The conference offers an overview on the development of the text and underlines the occurrence of new interpretations of traditional texts and messages already at the moment of composition and edition, in line with the different contexts in history. The New Testament is no different in its rendition of new biblical interpretations. The Constitution Dei Verbum recognises this character of the biblical text and stimulates its readers to interpret and contextualise the text in the perspective of their present context all over the world. Concrete examples of this contextualized rereading of the Bible come from the so-called “new hermeneutics” that emerged in Latin America from the “popular reading of the Bible” developed mainly in the context of the Basic Ecclesial Communities.

- The Bible as the first hermeneutical

moment

Modern exegesis, in its present state of development, has allowed, through its very diverse methods and approaches, not only to bring the reader close to the original message of the Bible, but it has also brought about the discovery of the processes and internal mechanisms of the formation and development of the biblical texts throughout the more than two thousand years that the process of formation of the Bible lasted.

Thanks, above all to the results of historical-critical analysis, we know today that most of the biblical texts are the final product of a complex literary process. These texts, as we know them in their present state, are the fruit of a long process of fusion, redaction, reelaboration, or reinterpretation of materials and traditions which already existed.

We can say with certainty that the interpretation of the Bible is not a recent phenomenon, but that it began already inside the Bible itself[1], and that our present effort at interpretation is simply the prolongation of a long process of interpretation that goes back to the origins of biblical history.

The great German biblical scholar of the last century, Gerhard von Rad (1901-1971), considered this redactional-interpretative process as something very normal – a vital necessity of the people of Israel, driven by their continual search and affirmation of their own identity as People of God: “Each generation discovers as its task, ever ancient and ever new, to understand itself as ‘Israel’. In a certain sense each generation had first to make itself Israel. As a general rule the children could recognises themselves in the image that their fathers had transmitted to them; but this did not dispense them from recognising themselves in the faith, as the ‘Israel’ of their own time and to present themselves as such before the Lord. To make this actualization possible the tradition had to be reformed in some points. Theological exigencies change and thus, for example, the elohistic redaction of the history of salvation appeared alongside that of the yahwist which was more ancient. The later generations searched for a theological sense in the great historical collections. To satisfy this desire the Deuteronomistic school introduced, during the exile, its own interpolations in the ancient narrative collections in order to interpret them and frame them. In this way the deposit of tradition gradually grew; new elements were added and they reinterpreted old ones. Alongside the primitive redactions there appeared more recent duplicates. No generation discovered a historical work that was autonomous and complete, but each one carried on working on what it had received[2]”.

A careful analysis of this process permits us to discover divine revelation not as a firm point in history, but in all its complexity and richness as a dynamic and continual process that develops in history across different generations[3].

- Theological traditions in Israel and their

intrabiblical rereading

Within the deposit of Israelite tradition gathered in the Bible we can find different theological streams, or, in other words, different streams of tradition that stretch across the different stages of the redaction of the texts of the Bible and that have their origin in the different groups that brought about this redaction[4].

In a short survey of the history of the people of Israel we will try to identify and analyse the development and interrelation of the different traditions and their contributions to the global deposit of the theological tradition of Israel reflected in the Bible.

- Premonarchical period

This is perhaps the most obscure period and the most disputed in the whole of the history of Israel. The origins of the people of Israel, the reality or not of the Patriarchs, the narratives of the origins… these are just some of the themes related to this period, that continue to be the subject of heated debates[5]. But considering the streams of tradition, the socio-cultural conditions of the time, the state of development and organization of Israel, these do not allow us to speak of the existence of any stable tradition. The only thing we can confidently assert is the progressive strengthening of monolatric worship of the Lord[6], based on the historical interventions of the Lord for Israel, around which Israel constructs its identity as People of God[7].

1.1.2. United monarchy

In the biblical tradition it is affirmed that in the last years of the second millennium and in the first of the first millennium before Christ there was established in Palestine and in the surrounding territories a united monarchical state, modelled on the great empires of the ancient Near East[8]. Also, in this period the confluence of different factors, political, religious and cultural, led to the birth in Israel of important streams of tradition that we will find in the whole Bible: the tradition of the worship of the Lord and the Israelite wisdom tradition.

- The tradition of the worship of the

Lord

During the reign of David there began what some have called the “syncretism of the state[9]”. With the objective of unifying the different peoples who formed the empire David had recourse to a series of religious measures, taken up and perfected afterwards by his successor Solomon. In the first place, he brought the Ark to Jerusalem, where he found a provisional place for it (2 Sam6). Gradually by means of the state worship the royal ideology was incorporated into the religion of Israel, bringing with it, among other things the divine promise of eternity made to the dynasty (2 Sam 7,15; Sl 2,7; and 110,4; Is 9,6f). On the other hand, the king appears presented with properly priestly roles, that will be strengthened in the time of Solomon with the construction of the temple, in which the king intercedes for the people and offers sacrifices (1 Kings 8). The foundations laid by David and Solomon for the organization of worship, of the temple and of the palace – with the central nucleus in Jerusalem – were very solid and survived until the fall of the kingdom in 587/586 BC.

In all this process it is almost impossible to separate the successive stages of the development of the stream of tradition of worship of the Lord. According to what Gerhard von Rad identified, “the solemn recitation of the principal moments of the history of salvation, either in the form of a creed, or as a parenetical address to the community, must have been an integral part of primitive Israelite worship”[10]. But, with time, other content will be added to this original nucleus. Thus, for example, in the litanies of Ps 136 we discover that in worship the salvific acts of the Lord are narrated and they do not begin with the liberation of Egypt but with the very act of the creation of the world. One could say therefore that the veneration of the Lord as creator of the world and biblical reflection on it come to form a part of this stream of tradition of the worship of the Lord with its origin in Jerusalem. But it is quite difficult to determine the moment when such additions took place[11].

1.1.2.2. Wisdom tradition

As regards the stream of Israelite wisdom tradition we again do not have sure information on its origins. With some certainty we can affirm that “wisdom is more ancient than Israel”[12] and that the origins of wisdom are to be found outside of Israel in the cultures of neighbouring peoples. But we might suppose that with the birth and establishment of the monarchy there would have arisen also in Jerusalem wisdom schools, in which future functionaries of the public administration would have received their formation. In this way Israel would be open to the international cultures and to the great sapiential streams of the time. One of the consequences of this opening would be the birth of works of historical literary character, the beginnings of proverbial wisdom and so much else[13], such as the composition of the history of Joseph at the end of Genesis[14].

1.1.3. The two kingdoms divided

Despite the division of the kingdoms after the death of Solomon, the two traditions mentioned above, with origin in Jerusalem, continue to develop.

In this period, we witness the birth of a new stream of tradition: the tradition of writing prophets[15]. At the start there are Amos, Isaiah and Micah. Later the tradition of the prophet Hosea will be added to this stream. This stream, both linguistically and thematically, is not compact and homogeneous as are the two mentioned before.

Its unity is based in the form of transmission of the message of the Lord, who speaks directly by the mouth of the prophet, and in the contents of the message transmitted, which are very similar in all the prophets and consist in the reinterpretation of the past and present with consequences for the future, under the prism of the covenant of the Lord with the people of Israel.

In this period too in the northern kingdom the ‘deuteronomistic movement’ is being forged. It will give rise to the deuteronomistic tradition which will develop and come to form part of the Israelite theological reflection by priestly circles in Jerusalem after the fall of the northern kingdom[16].

1.1.4. From the fall of Samaria to the exile

During this period, the wisdom tradition continues in a stable fashion without suffering major transformations. However, the cultic stream develops by incorporating in its reflection the drama of the fall of Samaria. This actualization takes place as an immediate and positive qualification of the new situation of the people of Israel.

In the same way, the prophetic tradition too does not fail to note the drama of the fall of the northern kingdom. However, in contrast to what happened in the cultic stream, the prophets generally interpret the fall of Samaria in a negative way and present it as the consequence of a deserved and inevitable judgement of God[17].

In this period the consolidation of the deuteronomistic tradition is of special importance and has lasting consequences. Its origins lie in the ‘deuteronomistic movement’ of the northern kingdom in the last period before the fall[18]. Directly and indirectly the deuteronomistic stream had great influence on the majority of the books of the Bible. It maintains that the destruction and captivity of Israel were the result of a long history of sin and infidelity to the covenant with the Lord. As immediate consequence of the guilt of the people came the matching punishment of God. It is taught also that only through conversion and obedience to the law can pardon and the blessing of God be achieved[19]. The principal exponents of this line of thought would be the principal promotors of the religious reform realized during the reign of king Josiah (2 K 22-23; 2 Chron 34,1-35,19)[20].

1.1.5. Exile

During the period of the exile the intellectual life of Israel had two great centres: those deported to Mesopotamia, and those who remained in Judah[21].

Among the exiles the prophetic stream flourished, and its message was adapted to the new political-religious situation. The prophets of this period, firstly Jeremiah and especially Ezekiel later on, try to maintain among the people a strong hope of restoration to their own land. Deutero-Isaiah, also belonging to the prophetic stream, composes his extraordinary poem of the return from exile, achieving an excellent assimilation of the universal elements of the cultic stream[22] with remarkable influence from the wisdom tradition. He interpreted the people’s afflictions as a remembering of Egyptian slavery and the journey through the desert. And so he described the liberation that was coming as a new exodus (Is 43,16,21; 48,20ff; 52, llff). The prophet does not suggest that Israel was worthy of liberation. Rather he maintains that, in the same way that the Lord at an earlier time had brought an unworthy people out of Egypt, so now he would call out of its new slavery a people blind and deaf (Is 42,18-21; 48,1-11) and would grant them an eternal covenant of peace (Is 54, 9ff). The new element in this way of thinking lies in the declaration that the rule of the Lord would be universal, extending not only over the Jews, but also over the Gentiles (Is 49,6). The literary and theological process of reelaboration and rereading of the ancient traditions in a new political and religious context, as exemplified by Deutero-Isaiah, is one of the principal characteristics of this period of the history of Israel.

Another important tradition in this period is the priestly tradition which promotes a vision of Israel as a cultic community built around the sanctuary. This tradition, even though it did not become a stream of tradition, will nevertheless have considerable political-religious influence in the period of the restoration[23].

In the territory of Palestine too, among the population which was not deported, the trauma of the destruction continued to be felt, here it is the deuteronomistic stream which prevails and is expressed in prayer and in penitential preaching (Ps 79; 105; 106; Lam).

1.1.6. Post-exilic period

The return of the exiles to their land and their meeting with the population which lived there bring about a new socio-theological situation in Palestine. As a consequence of this meeting there arise strong differences of opinion regarding the meaning of the deportation and the future organization of the people, which have repercussions in the works of restoration of the temple (Esd 3-5). It seems that the community was divided into two irreconcilable parts: those – mostly returned from the exile – who were driven by the old prophetic ideals and devotion to the faith and traditions of their fathers, and those – probably the mass of the native population – who had assimilated themselves so much to the Canaanite environment that their religion ceased to be Yahwism in its pure form. At the base of this problematic lay a strong moral and spiritual crisis arising from the tragedy of the deportation, which was expressed especially in the loss of hope[24]. The pious prayed for the intervention of God (Zc 1,12; Ps 44; 85), while others began to doubt the efficacy of the power of the Lord (Is 59,9-11; 66,5). In this context there came about a profound transformation of faith and tradition. All the streams of tradition mentioned up till now are maintained also in this period. But, with the passing of time and due to these crises and disturbances, there appear in the theological panorama of Israel two new principal orientations, that embrace and dominate all the others[25].

1.1.6.1. The theocratic stream

According to the ‘theocratic’ view, the temple and its cult constitute the fulfilment of the divine plan of salvation, just as the exilic prophets had proclaimed. This stream, encouraged principally by the priests, was the dominant view during the Persian period, during the political and religious reforms of Ezra and Nehemiah. It was intended to unite the population of Judah around the law and the worship of the Lord. In these circles the Pentateuch with priestly reelaborations and additions becomes a norm of faith and life; a work to be meditated upon, studied and put into practice and, at the same time, the law of the state for the province of Judah. In this ‘theocratic’ view the cultic stream finds its new location and is founded in it and it reflects the existential experiences of the individual in relation to God[26]. The sapiential stream too plays an important role in the realm of education and administration of this new Persian province.

1.1.6.2. The eschatological stream

Those who expound the ‘eschatological’ view are theologically more reserved in respect of the actual situation and hope rather for a new salvation that will come about in the future. They are situated in the continuation of the deuteronomistic stream, which according to all indications continues to be vibrant in the post-exilic period, and of the prophetic stream, through appropriation and reelaboration of earlier prophetic texts and new contributions (Third-Isaiah, Joel and Malachi)[27].

In the time of Hellenistic domination, due to a political-religious situation which is very complex, there comes about in Israel a gradual diminution of theological literary activity and the strengthening of existing traditions[28]. In this last period of Old Testament history, we witness the consolidation of the Old Testament into the form that we now know.

1.2. Inculturation of the Gospel

In the books of the New Testament we find a double process of rereading: the life, teaching, passion and resurrection of Jesus are reread and presented in different realities of the Christian communities of Asia Minor.

We find a model example of this process of rereading in the fourth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles, in the narrative of the meeting of Peter and John with the community after their liberation from prison (Acts 4,23-31). In the course of this meeting, which ends in a community prayer, Psalm 2 becomes the central axis of the prayer and its consequences. Psalm 2 appears in this short story in three different contexts: in its original context – the context of the past which is not concretely determined; in the context of the life of Jesus – who is seen by the praying community as the new subject of this psalm and, finally, in the context of the community itself – which also is identified with the anonymous protagonist of this psalm and thanks to him reveals his identity as the new ‘anointed of the Lord’.

There appears clearly in this story the process of rereading of the same biblical tradition in three different historical contexts. At the same time the Bible itself appears not only as a religious book which transmits divine revelation, but also as an important element in the process of construction of the identity of the new People of God.

In the narrative of the Pentecost event in the book of the Acts of the Apostles we meet this strange report: ‘there were in Jerusalem devout men, who were staying there who came from all the nations that there are under heaven. At that noise the people gathered and were filled with surprise on hearing them speak each one in his own language. Stupefied and amazed they said: ‘Are not all these men Galileans that are speaking? And yet how does each one of us hear them speaking in our own native language?’ (Acts 2.5-8). Pablo Richard in his commentary on the Acts of the Apostles[29] notes the fact that it is not the apostles who speak in different languages, but that those who witness are the ones who hear the message of the apostles each one ‘in his own language’. This allows Richard to consider Pentecost as ‘the Christian feast of the inculturation of the gospel’ – the message of God, that is unique, is expressed in different forms in different cultures. As we saw earlier, this process of reception of the universal message of the gospel in a concrete culture, which Pablo Richard defines with the term ‘inculturation’, and in the exegetical language is referred to as ‘rereading’ does not originate with the beginning of the movement of the disciples of Jesus, but is present in the whole biblical tradition.

- New contexts, new subjects, new

hermeneutics

From the very beginning of this survey we have been observing that in the books of the Bible there is an intense activity of interpretation. Earlier texts are interpreted with the intention of revitalizing them and illuminating with them the problematic that the community was living in a new historical context, we have seen that this process of rereading is found throughout the Bible, from the very beginning of its formation until the moment of the establishment of the biblical canon that closes the process of formation of the Hebrew Bible. But this process maintains its continuity also in the Christian communities.

The Dogmatic Constitution Dei Verbum of the Second Vatican Council makes us aware and motivates us to consider the different contexts in which the inspired text comes to be:

However, since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion, the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words. To search out the intention of the sacred writers, attention should be given, among other things, to “literary forms.” For truth is set forth and expressed differently in texts which are variously historical, prophetic, poetic, or of other forms of discourse. The interpreter must investigate what meaning the sacred writer intended to express and actually expressed in particular circumstances by using contemporary literary forms in accordance with the situation of his own time and culture. For the correct understanding of what the sacred author wanted to assert, due attention must be paid to the customary and characteristic styles of feeling, speaking and narrating which prevailed at the time of the sacred writer, and to the patterns men normally employed at that period in their everyday dealings with one another.

The document published in April 1993 by the Pontifical Biblical Commission on the interpretation of the Bible in the Church highlights the need for the process of rereading the biblical text in the context of the reader, calling it “actualization”: “Exegetes may have a distinctive role in the interpretation of the Bible but they do not exercise a monopoly. This activity within the church has aspects which go beyond the academic analysis of texts. The church, indeed, does not regard the Bible simply as a collection of historical documents dealing with its own origins; it receives the Bible as word of God, addressed both to itself and to the entire world at the present time. This conviction, stemming from the faith, leads in turn to the work of actualizing and inculturating the biblical message, as well as to various uses of the inspired text in liturgy, in “lectio divina,” in pastoral ministry and in the ecumenical movement”[30].

2.1. The “conversion of exegetes”

The document of the Pontifical Biblical Commission was the result of the growing awareness of exegetes of the need that their interpretive work should lead the reader to an appropriation of the biblical text, on the one hand, and of the different forms of incarnate reading of the Word of God performed in Christian communities in different parts of the world, on the other. The concern of the exegetes has been expressed very clearly, many years ago, to a group of Italian exegetes, by one of the great Bible scholars of the last century, Professor Luis Alonso Schökel: “If the exegesis is exhausted in the exact definition of the intention of the author, the interpretation internal to the Bible is not exegesis. But if the exegesis thus understood is only a part of the interpretation, is our job to be only exegetes or should we be interpreters? If we content ourselves with pure exegesis, who will interpret? Even more: without worrying about spirituality and prayer, will we understand the original meaning of the psalms? Strangers to social problems, will we understand the social meaning of Deuteronomy and many prophetic texts? Psychologically protected against the incidence of certain texts, will we better capture their original and permanent strength? In positive terms, open to the interpellation of Scripture, be it denunciation or hope, we will listen and transmit what is an integral aspect of the original meaning of the texts”[31].

2.2. The Bible in the life of communities

The greatest development of an updating reading of the Bible has nevertheless taken place in the context of the pastoral activity of the Church, in the environments of the basic Christian communities, especially in Latin America[32]. A special methodology of reading of the Bible in community has been developed there – “Popular reading of the Bible”[33] – whose main concern was to read the biblical texts in the context of the current problems of the community of faith: «The people are discovering that the Word of God is not only in the Bible, but also in the life. “God speaks today, mixed in things.” They discover that the main purpose of the use and reading of the Bible is not to interpret the Bible, but to interpret their life with the help of the light that comes from the Bible. Reading the Bible, the people have in their eyes the problems that come from the hard and suffering reality of their lives. The Bible appears as a mirror of what they are currently living. The people discover that the ground they walk on is the same, yesterday and today, and they establish, thus, a deep union between the Bible and their life. There is a mutual enlightenment: The Bible clarifies life and the life clarifies the Bible»[34].

[1] Cf. Grech, P., «Hermenéutica», NDTB, Madrid 1990, 733-734.

[2] von Rad, G., Teología del Antiguo Testamento, I. Las tradiciones históricas de Israel, BEB 11, Salamanca 71993, 164.

[3] Cf. Knight, D., «Revelation through Tradition», en Tradition and Theology in the Old Testament, ed. D. Knight, Philadelphia 1977, 143-180; Crenshaw, J.L., «The Human Dilema and Literature of Dissent», en Tradition and Theology, 235-258

[4] Cf. Steck, O.H., «Theological Streams of Tradition», en Tradition and Theology, Philadelphia 1977, 183-214.

[5] Cf. Ska, J.-L., Introducción a la lectura del Pentateuco, Estella 2012.

[6] Cf. Alt, A., Der Gott der Väter, Stuttgart 1929 = «The God of the Fathers», en Essays on Old Testament History and Religion, Oxford 1966, 1-77.

[7] Cf. Gottwald, N.K., The Hebrew Bible. A Socio-literary Introduction, Philadelphia 1985, trad. española, La Biblia hebrea. Una introducción socio-literaria, Barranquilla 1992, 100-228.

[8] Cf. Soggin, J.A., Storia d’Israele, Brescia 1984, trad. española, Nueva historia de Israel. De los orígenes a Bar Kochba, Bilbao 1997, 73-131.

[9] Cf. Soggin, Nueva historia de Israel, 104.

[10] Cf. Von Rad, G., «Das Formgeschichtliche Problem des Hexateuch», en Gesammelte Studien zum Alten Testament I-II, München 1961, 9-86.

[11] Cf. Zanchettin, C., «La creazione nell’Antico Testamento», RivB 20 (1972) 391-405; Von Rad, G., «El problema teológico de la fe en la creación en el Antiguo Testamento», en Estudios sobre el Antiguo Testamento, 129-139.

[12] Cf. Lusseau, H., «La literatura denominada sapiencial en Oriente», en Introduction à la Bible. II, ed. H. Cazelles, trad. española, Introducción crítica al Antiguo Testamento, Biblioteca Herder, vol. 158, Barcelona 1981, 578-615; Flor Serrano, G., «La sabiduría internacional y la sabiduría israelita», Reseña Bíblica 18 (1998) 5-11.

[13] Cf. Alonso Schökel, L., «Motivos sapienciales y de alianza en Gen 2-3», Bib 43 (1962) 295-316 = Hermenéutica de la Palabra. III. Interpretación teológica de textos bíblicos, Bilbao 1991, 17-36.

[14] Cf. Von Rad, G., «La historia de José y la antigua hokma», en Estudios sobre el Antiguo Testamento, 255-262.

[15] Cf. J.L. Sicre, J.L., Profetismo en Israel, Estella 1992, 249-299.

[16] Cf. Steck, 202.

[17] Cf. Sicre, 301-321.

[18] Cf. Lohfink, N., «Bilancio dopo la catastrofe. L’opera storica deuteronomistica», en Wort und Botschaft des Alten Testaments, ed. J. Schreiner, Würzburg 31975, trad. italiana, Introduzione letteraria e teologica all’Antico Testamento, Cinisello Balsamo 51990, 338-357.

[19] Cf. Steck, 207.

[20] Cf. Soggin, Nueva historia de Israel, 305-312.

[21] Contrary to the “official” version of the story we find in the Bible, most modern authors, based on the results of the latest research, agree that not all of them were taken to Babylon and that a large part of the the population was left in Juda. Cf. Soggin, Nueva historia de Israel, 318-323; Gonçalves, F.J., «El “destierro”. Consideraciones históricas», EstBíb 55 (1997) 431-461.

[22] Throughout the book of Deuteroisaias the motive of creation, which is one of the main elements of the cultic current, appears with great force.

[23] Cf. Soggin, Nueva historia de Israel, 346-350.

[24] Cf. Bright, J., A History of Israel, Philadelphia 31981, trad. española, La historia de Israel, Bilbao 81985, 429-444.

[25] Cf. Steck, 208-212.

[26] Cf. Von Rad, G., «“Justicia” y “vida” en el lenguaje cúltico de los salmos», en Estudios sobre el Antiguo Testamento, 209-229.

[27] Cf. Steck, 211.

[28] The only exception would be the apocalyptic contributions in this era. Cf. Soggin, J.A., «Profezia ed apocalittica nel giudaismo post-esilico», RivB 30 (1982) 161-173.

[29] Richard, P., El movimiento de Jesús antes de la Iglesia: una interpretación liberadora de los Hechos de los Apóstoles, Santander 2000.

[30] Pontifical Biblical Commission, The interpretation of the Bible in the Church, Vatican 1993.

[31] Alonso Schökel, L., «La Biblia como primer momento hermenéutico», en Hermenéutica de la Palabra. I. Hermenéutica bíblica, Academia Cristiana 37, Madrid 1987, 151-161

[32] Stefanów, J.J., «Hermenéutica bíblica o inculturación del Evangelio», Reseña Bíblica (2014), 41-49.

[33] Cf. Mesters, C., «Lectura popular de la Biblia», BDTL, Santiago 1992, 157-173; Richard, P., «Lectura popular de la Biblia en América Latina. Hermenéutica de la liberación», RIBLA 1 (1989) 30-48.

[34] Mesters, 160.

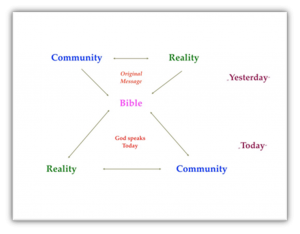

The methodology used in this form of reading is very simple: the biblical text is read in its “yesterday”, in its original socio-historical-cultural context, to discover the original experience of faith from which the text was born. The next step is to reread this text, together with the experience of faith that originated it, in the “today” – in the reality of the community that meets to illuminate its life with the light of the Word of God.

2.3. The “new hermeneutics”

The experience and methodology of the basic Christian communities, received and developed by the Bible scholars committed pastorally, has given as a fruit the development of the “new hermeneutics”[1]: – ways of reading of the books of the Bible from the reality the reader, or better said, from the prospective of the different groups of readers and from their reality. In this way the diverse specific hermeneutics have been constituted: indigenous hermeneutic[2], peasant hermeneutics[3], urban hermeneutic[4], feminist hermeneutic[5], that with time has developed in the hermeneutics of gender, youth hermeneutic, black hermeneutic[6]… – different ways of approaching the biblical text that responds to the originality and sensitivity of the reading subject and that leads him to encounter God through the dialogue between the biblical text and the identity of the lector[7].

This concern to update and make alive the texts of the Bible, in order to illuminate with them the current concerns and problems of the community, corresponds to the way of approaching the biblical tradition that we have observed in the study of the biblical traditions. A text that is preserved without being touched or used, moves away from the community that keeps it “intact.” A text that is used, as it comes into contact with life, is changing its meaning. In both cases, time and distance affect the text, modify its original meaning and demand a new type of interpretation. This process of interpretation is carried out in the tension between two fidelities: fidelity to the original meaning of the text and fidelity to the current reader[8]. The fruit of this process of interpretation is again a living and interpellating text, capable of “lighting the heart in love of God” (DV 23).

- Listening to the Word of God

In the post-synodal exhortation “Verbum Domini” Pope Benedict XVI invites the Church to put the Word of God at the centre, to make it the fundament on which the Christian community is built. He invites the Church to listen to God who in different ways directs us his Word: “While the Christ event is at the heart of divine revelation, we also need to realize that creation itself, the liber naturae, is an essential part of this symphony of many voices in which the one word is spoken. We also profess our faith that God has spoken his word in salvation history; he has made his voice heard; by the power of his Spirit “he has spoken through the prophets”. God’s word is thus spoken throughout the history of salvation, and most fully in the mystery of the incarnation, death and resurrection of the Son of God. Then too, the word of God is that word preached by the Apostles in obedience to the command of the Risen Jesus: “Go into all the world and preach the Gospel to the whole creation” (Mk 16:15). The word of God is thus handed on in the Church’s living Tradition. Finally, the word of God, attested and divinely inspired, is sacred Scripture, the Old and New Testaments. All this helps us to see that, while in the Church we greatly venerate the sacred Scriptures, the Christian faith is not a “religion of the book”: Christianity is the “religion of the word of God”, not of “a written and mute word, but of the incarnate and living Word”. Consequently, the Scripture is to be proclaimed, heard, read, received and experienced as the word of God, in the stream of the apostolic Tradition from which it is inseparable”[9].

(Jan J. Stefanów is a Divine Word Missionary from Poland. He studied in Madrid (theology) and obtained a degree in biblical theology from the Pontifical Gregorian University (Rome). He worked in Ecuador and Poland. Since the beginning of 2014 he is the General Secretary of the Catholic Biblical Federation, based in Munich (Germany).

[1] Croatto, J.S., «Las nuevas hermenéuticas de la lectura bíblica», Alternativas. Revista de análisis y reflexión teológica 5 (1998), 15-36.

[2] Carrasco A, V., «Antropología indígena y bíblica: «Chaquiñan» andino y Biblia», Revista de Interpretación Bíblica Latinoamericana (1997), 24-44; da Silva, V., «Hermenêutica indígena e bíblica», in Reimer, H. – da Silva, V., ed., Hermenêuticas bíblicas. Contribuições ao Congresso Brasileiro de Pesquisa Bíblica, São Leopoldo 2006, 206-211; Bremer, M., La Biblia y el mundo indígena, Asunción 1998.

[3] Cañaveral Orozco, A., «Aportes para una lectura camesina de la Biblia», Alternativas. Revista de análisis y reflexión teológica 5 (1998), 185-202; Cañaveral Orozco, A., El escarbar campesino en la Biblia, Quito 2002.

[4] Navia Velasco, C., La ciudad interpela a la Biblia, Quito 2001; Torres, F., «Caminos de pastoral bíblica», Teológica Xaveriana (2002), 641-662.

[5] Mena López, M., «Hermenéutica bíblica negra feminista», in Torres, F., ed., Hermenéutica bíblica latinoamericana. Balances y perspectivas, Questiones. Documentos de Teología Latinoamericana, Bogotá 2002, 117-136; Aragón Marina, R., ed., «Teologia con rostro de mujer», Alternativas. Revista de análisis y reflexión teológica 7 (2000), 1-338.

[6] Padilha, G., «Hermenêutica bíblica negra e seus desafios», in Mena López, M. – Nash, P.T., ed., Abrindo sulcos: para uma teologia afro-americana e caribenha, São Leopoldo 22003, 110-130; Mena López, M., «Hermenéutica bíblica negra feminista», in Torres, F., ed., Hermenéutica bíblica latinoamericana. Balances y perspectivas, Questiones. Documentos de Teología Latinoamericana, Bogotá 2002, 117-136.

[7] Salas Astraín, R., «Hermenéuticas en juego, identidades culturales y pensamientos latinoamericanos de integración», Polis. Revista Latinoamericana (2007); Carroll Rodas, M.D., «La Biblia y la identidad religiosa de los mayas de Guatemala en la conquista y en la actualidad: Consideraciones y retos para los no-indígenas», Kairos (1996), 35-58.

[8] Cf. Alonso Schökel, L., «La Biblia como primer momento hermenéutico», 154-155.

[9] Verbum Domini, 7